Exploratory Fly Fishing in León, Spain

When the chance to explore a new European fly-fishing destination came my way, I didn’t hesitate. Within days, tickets were booked, bags were packed, and my sights were set on northern Spain’s León province, part of the autonomous community of Castile and León. This is a region steeped in history and famed for its centuries-old fly-fishing tradition.

My final destination was the small town of Cistierna, nestled about 60 kilometres northeast of León in the foothills of the Cantabrian Mountains and the Picos de Europa. But as with any good adventure, getting there was half the story.

Planes, Trains, and Automobiles

The journey began at Gatwick Airport with a brisk two-hour flight into Madrid, where I met up with my fellow explorer, Peter. Together, we navigated the bustle of the capital to reach Chamartín Station, ready to catch the afternoon train north.

The 1 hour 45 minute ride to León gave us time to get acquainted. Conversation naturally flowed toward fishing, as it always does, but also drifted into the ups and downs of life. Outside the window, the landscape unrolled in shades of dusty ochre and sun-scorched brown, reminding me strongly of Southern Africa. That familiar palette brought with it a wave of nostalgia, and before long we were deep in conversation about home, its challenges, and its enduring beauty.

Arrival at León station snapped us back to the present, where we were greeted by our enthusiastic hosts, Diego and Dani from Fly Fishing León. Smiles, handshakes, and a quick loading of luggage later, we were tucked into Dani’s SUV and on the final stretch to Cistierna.

As we drove deeper into the countryside, Diego painted a vivid picture of the days to come; rivers winding through quiet bucolic valleys, traditional Spanish dry-fly techniques, and the promise of wild trout rising in crystal-clear waters. After a full day of planes, trains, and automobiles, fatigue should have set in, but the growing anticipation pushed it aside, the adventure was just beginning.

The Río Esla

As the evening light began to fade, Dani suddenly exclaimed in his enthusiastic, broken English that we simply had to make a pit stop. The reason? To lay eyes on the river that would become the heart of our adventure, the magnificent Río Esla.

The Esla is the largest of the southward-flowing rivers that spill out of the Cantabrian Mountains, and the biggest tributary of the mighty Douro, which winds its way through Spain and Portugal before meeting the Atlantic at Porto. Here in its upper reaches, where we would spend the next few days, the Esla cuts a serene path through the valleys.

Bumping along half-forgotten dirt tracks, we eventually rolled up to a weir that diverted part of the river into irrigation canals, lifelines that connect the Esla not only with the surrounding farmland, but also with its sister river, the Río Porma, a few valleys to the west. Diego explained that fishing wasn’t allowed in this particular stretch, and from the looks of it, the fish knew it!

Almost immediately, we spotted broad-shouldered brown trout gliding effortlessly between the verdant weed beds. Then, just downstream, a cruising school of large Iberian barbel caught my attention. For a South African raised on a steady diet of yellowfish, the sight was hypnotic. I asked Diego about targeting them, and was surprised to learn that they, too, are typically pursued with nymphing techniques, though on 7- or 8-weight outfits, quite a step up from the 10-foot 3-weights we use on the turbid waters of the Vaal-Orange system back home for fish of similar size.

Diego’s clear respect for these powerful cyprinids, only whet my appetite more, but I’d have to scratch that itch another time. Sadly, it wasn’t their season, and this trip was about autumnal dry-fly fishing for wild brown trout.

As dusk settled fully into night, we climbed back into the SUV and continued northward. Soon, the lights of Cistierna appeared, a sleepy mountain town that would be our base camp, our home, and the backdrop to three days of fishing adventure.

Hotel Puerta Vadinia

Rounding a final bend, Dani and Diego’s faces lit up with pride as we pulled up to the Hotel Puerta Vadinia, their recently refurbished hotel and restaurant. The building stood tall and welcoming against the darkening mountain backdrop, a clear labour of love.

After a quick tour of the facilities — a well-stocked bar, cosy restaurant, small gym, garden, and even a function space — we were shown to our rooms. As promised, mine was spacious, spotless, and exceptionally comfortable. After a long day of travel, it was exactly what I needed. This would do nicely!

A quick wash and change later, I re-joined Peter and our hosts downstairs at the bar. Cold San Miguels were pressed into our hands, and conversation soon turned lively. It was then we were introduced to Alain, a soft-spoken Frenchman and a member of the guiding team.

Diego leaned in with a grin and a warning not to be fooled by Alain’s quiet, almost reserved demeanour. Among the team, he was known as “El Cormorán”… The Cormorant. And as I’d soon discover, the nickname was more than earned. He would prove to be, without exaggeration, one of the fishiest dudes I’ve ever met.

Feasts and feathers

Dinner that night was a feast of traditional Leonese cuisine, hearty and deeply rooted in the region’s history. Among the many dishes that arrived at the table, my personal favourite was cecina, a cured beef delicacy unique to León. Smoky, savoury, and utterly delicious, it was the kind of food that demanded a second helping.

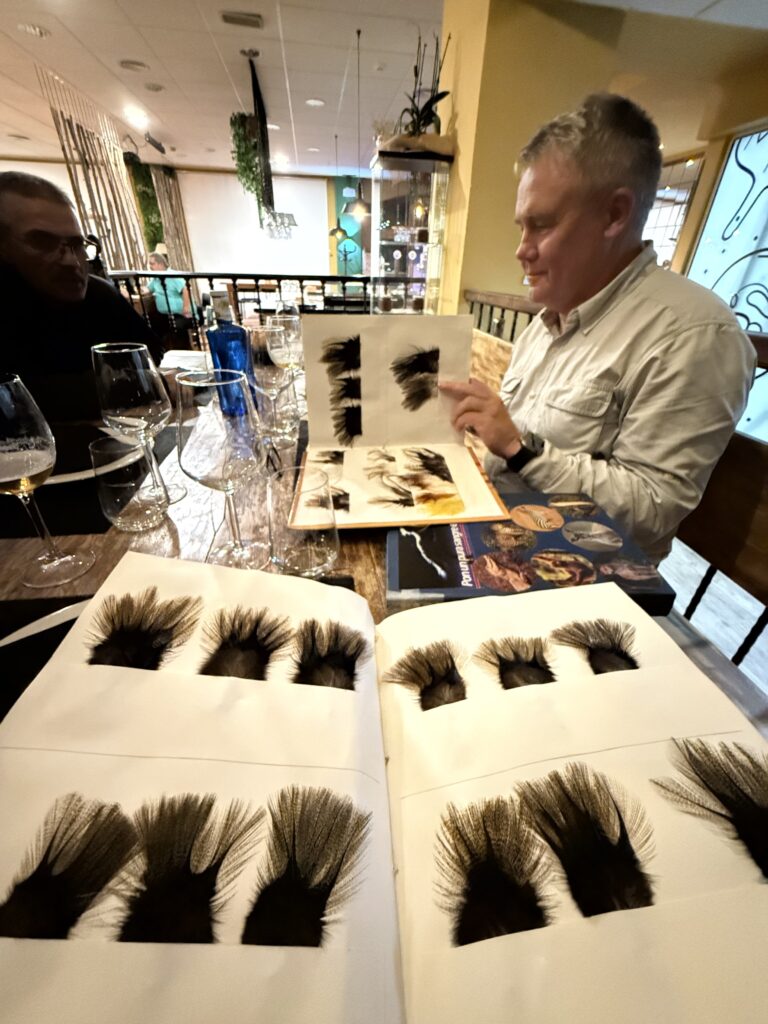

Between bites, the conversation naturally turned to the day ahead: which stretches of river we’d explore, what tactics might work best, and of course, the flies. At that, Dani excused himself with a sly grin and disappeared into the back room. Moments later he returned, carrying three oversized binders, the kind a stamp collector might use to store their tiny treasures… but these weren’t filled with stamps.

Inside was a trove of another of León’s most famous exports, at least amongst fly anglers: gallo de León (also known as coq de León). For centuries, these feathers, plucked from roosters raised only in this region, have been revered by fly tyers across Europe.

The history is remarkable: since at least the 17th century, local breeders have painstakingly cultivated these birds, producing feathers prized for their durability, translucence, and lifelike movement in the water. For wet flies and nymphs in particular, coq de León has long been considered the gold standard, and to this day it remains one of Spain’s proudest contributions to global fly tying.

Dani, with mock seriousness, told us he knew exactly how many feathers each book contained, so we’d better not get any ideas. Laughter followed, and then he pulled out a fly box containing a wonderful collection of traditional Leonese wet flies, every pattern incorporating coq de León in some way.

It was a living connection between centuries of tradition and the adventure that awaited us in the morning.

First Casts

Morning came quietly to Cistierna. Over coffee, Diego joked that the fish here kept Spanish time and didn’t wake up before 10 a.m. I was perfectly fine with that. After the long travel day behind us, a relaxed start felt just right.

Our first beat on the Esla lay only about twenty minutes away, but Diego insisted we take the scenic route. We wound through a patchwork of sleepy rural villages and farmsteads, the countryside glowing in its autumn colours of gold, copper, and crimson. The air was crisp, clean, and charged with that unmistakable sense of promise that only a new fishing day can bring.

When we reached the river and began setting up, we noticed the first sporadic rises dimpling the surface. Time to talk tactics. The plan was to fish small mayflies, sizes 18–20, tied in the classic Spanish style, with the possibility of a caddis hatch to keep things interesting.

Our chosen water was a long, steady glide along the far bank. As I was there to document the trip as well as fish, I started by shadowing Peter and Diego, camera in hand. Immediately, one thing was clear: this was a healthy river system, alive in every sense. Weed beds swayed hypnotically in the cold, steady flow; aquatic invertebrates darted between the fronds; and schools of tiny baitfish shimmered just beneath the surface. This was no manicured chalkstream like those of southern England, this was a wild river, full of wild fish.

Peter soon hooked into a delicate riser tucked tight against the far bank. In short order, he brought a beautiful little wild brown trout to hand, the first of the trip. Spirits were high, but as the morning wore on, the light began to fade behind gathering clouds, the temperature dropped, and the hatch began to slow.

During the lull, I took the opportunity to launch the drone and capture the Esla from above, a ribbon of gold and green winding through the autumn valley. My novice nerves didn’t make it easy, but I managed to land the drone safely with a sigh of relief.

Moments later, from upstream, Diego’s excited shout cut through the still air: another hatch was starting. Time to fish.

I grabbed the 4-weight, tied on a size 18 olive, and began stalking upstream. Between two lush weed beds, a single fish was rising steadily. My first cast fell short; the next drifted perfectly down the seam. The rise came right on cue. A confident splash, the fly vanished, and I lifted into solid resistance.

“Good fish!” Diego called as he splashed toward me. The trout surged for the weeds, using every ounce of the current to its advantage. On 7X tippet, there was no forcing the issue. Despite careful pressure, the fish buried itself deep in the vegetation. A few tense seconds later, the line went slack. Gone.

A brief pang of disappointment, yes, but also that unmistakable buzz that comes from being in the game. It was a fine start to the morning, and the river was alive with promise.

As we moved upstream, I stowed my rod and fell in behind El Cormorán with my camera. I asked Alain how he’d fared so far. In broken English, he said he’d landed eight and missed “many, many more.” Watching him cast was a masterclass; smooth, efficient, deadly accurate. His line cut the air in tight, elegant loops, the fly landing exactly where it needed to. He made it look effortless, which, of course, is the surest sign of a maestro at work.

It quickly became clear how he’d earned his nickname. He could spot rises invisible to the untrained eye — faint dimples or subtle swirls that I would have mistaken for shifting current. A quick cast, a precise drift, and moments later his rod would bend.

If I wanted to succeed on the Esla, I realised, I’d need to sharpen my senses. This was delicate, technical fishing, and I needed to up my game.

Welcome to león

The rest of the morning proved tricky. Despite a few promising rises and plenty of effort, only a handful of fish came to hand. By late morning, the consensus was clear: it was time for a break.

We spread out a simple but delicious riverside lunch — fresh bread, bananas, slices of smoky cecina, and generous wedges of tortilla de patatas. Few meals taste better than those eaten beside a river, especially after a morning of hard fishing. As we ate, we speculated about the quiet spell; changing pressure, cooling water, or perhaps the fish just weren’t in the mood. Whatever the reason, our hosts decided a change of scenery might do us good.

We packed up the gear, loaded into the SUVs, and set off once more. The afternoon beat lay not far from where we’d first glimpsed the river the evening before. Here, the Esla was peppered with small islands, creating a mosaic of water types: slow, glassy glides toward the far bank, and lively, riffled sections threading between us and the islands.

Peter and Diego opted to work the slower glides, while Dani and Alain disappeared upstream to give us space. I stayed behind to fly the drone briefly, gathering a few more aerial shots, before turning my attention back to the river.

The quicker water in front of me showed signs of life, occasional rises betraying trout feeding in the broken current. It looked tricky to fish, with crosscurrents and shifting seams, but I couldn’t resist. After a few experimental casts and some careful mending, I finally found the right drift. On the very next pass, a small brown trout rocketed up and smashed the fly.

I grinned as I released the little wild fish, foolishly thinking I had figured them out. Working my way upstream, I began to pick out more likely looking water, but the takes were so deceptively subtle. More than once, my fly simply vanished without a swirl or splash, leaving me striking at air. After missing the fifth fish in a row, I couldn’t help letting out a few choice words.

From somewhere upstream came Diego’s laughter and a good-natured shout:

“Welcome to León, my friend!”

Storms and Reflections

As afternoon faded into evening, the sky began to darken, a heavy slate-grey curtain rolling in over the mountains. The first sporadic drops of rain splattered the water, and Diego glanced skyward with a knowing look. “We might be in for a downpour,” he said.

We took the hint and made for the cars. By the time we’d stripped off our waders and packed away the gear, the heavens opened. A powerful squall swept through the valley, wind whipping the rain sideways as we scrambled into the SUVs, laughing and shouting over the noise.

The drive back to Cistierna was a blur of wipers, mist, and conversation. The day replayed in flashes: the eats, the misses, the lessons learned. The kind of reflection that comes easily when you’re tired, damp, and content.

Back at the hotel, we were rewarded with a feast fit for weary anglers. Crisp calamari to start, followed by melt-in-the-mouth braised pork cheeks. Over dinner, Dani introduced us to José, his business partner and co-owner of the Hotel Puerta Vadinia. Conversation turned to the challenges of running a hotel in a small mountain town, and José spoke passionately about his hopes to further develop fly fishing tourism in the region, an industry with deep roots but still untapped potential.

As the evening wore on and plates were cleared, fatigue set in. We said our goodnights and headed upstairs, lulled by the steady drumming of rain against the windows.

Tomorrow, the Esla would be fresh, the air washed clean, and with any luck, the fishing even better.

Coto DE PESCA

The next morning, as I was hunting down a much-needed espresso, I heard the low murmur of conversation coming from behind a screen in the corner of the dining room. Curious, I peeked around to find Peter and Alain deep in discussion… or rather, deep in translation. Armed with Google Translate and plenty of gestures, they were managing a kind of linguistic truce that was equal parts charming and chaotic.

Alain was at the tying vise, deftly crafting a few more flies for the day ahead. I joined them, watching as El Cormorán worked with quiet concentration, his hands moving with the same precision he showed on the water.

With meticulous attention to detail, he demonstrated how he ties the Spanish-style mayflies that are the cornerstone of local dry-fly fishing. Each was a study in elegant simplicity: a coq de León tail, naturally, paired with a body dubbed lightly with rabbit fur mixed with olive silk, and natural CDC wings split by a slim sighter of bright floss. A tried-and-true pattern, deceptively simple, and incredibly deadly.

With some more help from Google Translate, we chatted about flies, materials, and techniques as the first light of dawn spilled through the windows. The smell of coffee mingled with the faint scent of dubbing wax, a strangely perfect combination. Before long, Diego appeared, signalling that it was time to roll.

Our destination for the day was the small town of Gradefes, about 25 kilometers away, where we’d be fishing our first coto.

In Spain, most rivers are open to the public for fishing, provided one holds a valid license. However, certain stretches, known as cotos, operate under a reservation system to help manage angling pressure and preserve fish stocks. Anyone can apply, but the best sections are often fiercely contested, with demand so high that the government’s booking website routinely crashes on opening day.

Fortunately, Diego had secured our permits well in advance. He grinned as he explained that this particular coto was known for large, powerful browns, especially near the upper reaches below a massive irrigation weir.

It sounded promising, and after the previous day’s near misses, I was more than ready for a bit of redemption.

Arrival at Gradefes

The drive to Gradefes took us through rolling farmland and sleepy hamlets, the morning light slanting low across the fields. As we entered the town, a beautiful tree-lined avenue guided us toward the main bridge over the Esla, our gateway to the day’s fishing.

Crossing the bridge, we could already see several local anglers wading the pools downstream, their fly lines catching flashes of sunlight as they cast. Dani explained that the water downstream of the bridge was “libre” — open to anyone with a license — while the stretch upstream was our reserved coto. It was encouraging to see how alive the local fly-fishing scene was, but I couldn’t deny the relief of knowing we’d have a bit of space and solitude on our own stretch.

A quick right turn took us through a series of narrow winding streets, and before long we were bumping along a dirt track that cut through a small plantation. The trees swayed in the freshening breeze, and Diego frowned slightly as he watched the leaves flicker.

“I hope this wind doesn’t pick up,” he said ominously, half to himself, half to us.

We parked near the top of the beat and climbed out to survey the water below the weir. It was an impressive sight, the Esla spilling powerfully over concrete into a deep, swirling pool. In the back-eddy directly below us, I immediately spotted one of the large trout Diego had hinted at suspended lazily in the recirculating current.

A promising start, though, as Diego quickly pointed out, this particular pool was off-limits, lying within the no-fishing zone immediately below the weir. He gestured to a pair of faded signs on either bank marking the upper boundary of the coto. “But don’t worry,” he said, smiling. “They move in and out all day. There are more like him below.”

Still, this upper stretch was too exposed to the strengthening wind, so we decided to relocate. Piling back into the cars, we followed the track downriver toward the lower end of the beat, just above the road bridge we’d crossed earlier. Here, the trees offered welcome shelter, and the water glided smooth and quiet in the lee of the wind.

After sending the drone up for a few minutes to capture the morning light over the river, I joined Peter and Diego a short distance upstream, rods in hand and anticipation in the air.

Battling the Wind

By late morning, the wind had stiffened into a relentless gust funnelling down the valley, scattering a steady carpet of yellow leaves across the water. They drifted in tangled ribbons along the seams, making it nearly impossible to spot rises, and even harder to get a clean drift.

We worked our way slowly upstream, picking apart likely-looking water, but there was no sign of surface activity and no fish to hand. An hour passed in stubborn persistence. I busied myself shooting B-roll while Pete and Diego conferred quietly midstream, both frowning into the breeze.

Finally, Diego sighed, his voice half lost in the wind.

“Let’s go back up, near the weir,” he said. “Hard to cast there, but I promise you, there’ll be fish.”

That was all the convincing we needed. We headed back to the cars and made our way upstream.

As expected, conditions at the upper beat were diabolical, the wind tearing through the exposed channel below the weir, but sure enough, there were fish feeding if you knew where to look. Diego soon spotted one: a steady, confident riser in the middle of the river in a slow pocket just beside a fast-moving run.

Due to the nature of riverbed, with some deep fast-moving channels to navigate around, the fish could only be approached from one angle, so I waded into position to plan my assault. It wasn’t going to be easy. Between us ran a tongue of heavy current that would drag the fly almost instantly, no matter how big a mend I threw. And then there was the wind… an unpredictable tempest threatening to drop my fly anywhere except the tiny window I needed.

After a handful of appalling casts, I forced myself to stop. Better to wait and let the fish keep feeding, building confidence. I watched for nearly ten minutes, studying the rhythm of its rises, waiting for the wind to ease. My plan was risky but simple: throw a cast with plenty of slack, land the fly practically on the fish’s head, and buy a few seconds of clean drift before the current took over.

When the wind finally dipped to a manageable level, I took a deep breath and fired.

Too far.

Another cast. This one landed close, not perfect, but close enough. The water boiled beneath my fly. My pulse spiked, the world shrank to a single moment of movement.

From behind me came a triumphant yell, “¡Sí!” as Diego pumped his fist in the air. I lifted the rod and felt a heavy surge on the line… then, heartbreak. The rod sprang back, the fly arcing free into the wind.

I groaned, glancing back to see Diego with his head in his hands, a wry grin spreading across his face.

“Unlucky!” he shouted over the whipping wind.

Devastated? Absolutely. But also completely exhilarated. There’s no better feeling than outsmarting a wise old fish, even briefly, proving, if only for a heartbeat, that you’re a step closer to cracking the code of a wild river.

The rest of the morning followed much the same rhythm, equal parts frustration and exhilaration. Peter and I each had a few more shots at rising fish, but nothing would stick. The wind toyed with our casts, the trout toyed with our patience, and by the time we made our way back to the cars, we were both shaking our heads and laughing at the futility of it all.

Still, as we packed away the rods and compared notes, we couldn’t help but admire the quality of the fish we’d encountered. Wild, wary, and beautifully conditioned, the kind of trout that make you earn it. We’d been soundly humbled, and we both knew it.

Lunch was a simple affair, fresh bread and salmorejo, a wonderfully thick, chilled tomato-and-garlic soup typical of northern Spain. Sitting around the small table, we recapped the morning while Dani and Alain rolled in from their own stretch. Judging by their expressions, they’d had a similarly tough session. A round of knowing smiles was exchanged; no one had cracked the code yet.

Conversation soon turned to potential beats we could visit that afternoon that would fish well in these challenging conditions.

A Change of Scene

After a brief but spirited debate in rapid-fire Spanish, consensus was reached. Dani clapped his hands, Diego nodded, and just like that, we were on the move again. We piled into the SUVs, spirits lifted by the promise of new water.

A quick pit-stop for coffees reinvigorated us, and soon we were winding our way through a patchwork of fields and irrigation canals. When we finally reached the river, the Esla revealed a different face; smaller, more intimate, and somehow more inviting.

“This,” Diego explained, gesturing ahead, “is just a side-channel. The main river runs beyond that island.”

In front of us, a small weir diverted part of the flow into yet another irrigation canal. Below the spillway, the water tumbled noisily into a tangle of overgrown vegetation, creating a frothy pool that looked alive with energy, but impossible to fish. Upstream, however, the tone changed completely. A tranquil pool, its surface glassy and reflective, broken only by the delicate dimples of rising fish, and the gentle undulations of the weeds just beneath the surface.

Shielded from the wind by the surrounding trees, the water lay calm and mirror-like, reflecting the riot of autumn colours that blazed from the banks. It felt like we’d stumbled upon a secret, a quiet pocket of serenity carved from the larger, wilder Esla.

While Peter worked the near bank, I decided to try my luck across the way. I edged carefully over the weir, and waded quietly toward the far bank. Just beyond a tangle of submerged branches, a faint ripple caught my eye; a subtle rise, almost imperceptible unless you were really looking for it.

I dropped a tentative cast into the feeding lane. The drift looked good. Then another, perfect. Both were ignored. I paused, watching, thinking. A quick change to the tiny caddis pattern, a deep breath, and another cast.

Boom! A confident take shattered the stillness. I lifted the rod, felt the pulse of life on the other end, and grinned. After a brief, spirited tussle, a feisty little brown trout came to hand, gleaming in the afternoon light.

A wave of relief washed over me. After a morning of near-misses and fickle winds, it finally felt like the rhythm of the river was tilting back in our favour.

Peter and I continued working the pool, picking up a few more fish each, the rhythm of the afternoon slowly settling in. Further upstream, loud splashes punctuated the quiet, as sizable fish periodically launched themselves into the air, announcing their presence with authority.

I tried to wade closer, but the pool deepened beyond the reach of my waders. Diego and Peter decided to give it a go. I stepped back, trading my rod for the drone, hopeful I could capture the impending hook-ups from above.

Pass after pass, nothing. The drone hovered expectantly, the fish elusive beneath the surface. Then the inevitable: the low battery warning blared. Begrudgingly, I guided the drone back to safety. As I began packing it away, chaos erupted. Dani, Peter, and Alain shouted in excitement.

Diego was in.

My timing couldn’t have been worse. With the drone offline, all I had was my phone to document the fight. Upstream, Diego wrestled with a truly formidable fish, his rod bending and thrashing with every violent head shake. I crashed through the brambles and undergrowth on the opposite bank, desperate for a better angle. Arms scratched, heart pounding, I burst through only to find Diego wearing a worried expression.

“He’s wrapped me in the roots of that tree!” he called out, straining to coax the fish free from the tangled maze it was hiding in. He tried applying pressure from every angle, but the fish refused to budge.

Then… slack line.

Diego’s shoulders slumped. Once again, the river had won. “Welcome to León.” I quipped.

Diego chuckled as a wry smile slowly spread across his face. “Now you’re getting it,” he said. And in that moment, I understood completely: this was wild fishing in every sense; unpredictable, humbling, and utterly exhilarating.

La Camperona

After that, we all agreed to call it a day. On the drive back to Cistierna, conversation turned reflective, the ups and downs of the day replayed against the hum of the tyres and the fading afternoon light. The fishing had been challenging, no doubt, but it had also been deeply engaging. I was beginning to understand why the Spanish are highly regarded anglers, not only for their dominance in competitive fly fishing, but for their broader contributions to the techniques, tactics, and even the philosophy of the sport itself.

As these thoughts percolated in my mind, I caught sight of the distant peaks glowing softly on the horizon. Dani glanced at me with a grin. “Would you like to visit La Camperona? It affords wonderful views of the Picos de Europa.”

Peter and I didn’t hesitate. With renewed purpose, we drove higher into the foothills beyond Cistierna, eager to see more of this quietly magnificent region.

We passed through a series of small, half-deserted villages, ghostly reminders of a different era. Crumbling façades, shuttered windows, streets too quiet.

“Mining,” Dani explained. “All of these towns were company-owned. When the mines shut down in the ’70s, the people left… and the towns never recovered.”

It was a familiar story, one that echoed places I’d seen before; communities built on industry, left hollow when the work dried up. We nodded in silence as the road wound higher into the mountains.

Eventually, we turned off onto a narrow track that snaked through dense forest. A few steep switchbacks later, the trees gave way and the world opened up, we’d broken through the treeline, approaching the summit of La Camperona. The peak was crowned with aerials, antennas, and a small fire lookout station, a utilitarian outpost atop wild beauty.

As soon as we stepped out of the car, an icy alpine wind hit us full in the face. Pulling our jackets tight, we trudged the short distance to the summit, marked by a simple piles of stones left by previous visitors.

The view was breathtaking. A 360-degree panorama stretched before us, bathed in the soft, pastel hues of the fading evening. Dani pointed out the old mining towns scattered across the valley far below, their stories etched into the landscape. We stood there for a while, silent, just taking it all in.

Eventually, as the last light drained from the sky and the cold began to bite, we made our way back down to the car. The promise of warm meals and cold beers beckoned us home to Cistierna.

Evening Reflections

That evening the conversation was full of good-natured ribbing about lost fish, mistimed strikes, and the ones that got away. Over a delicious starter of pulpo a la gallega; tender octopus with potatoes, smoked paprika, and olive oil, followed by a hearty chicken and seafood paella, we laughed, compared notes, and raised quiet toasts to the mysteries of the Esla.

Tomorrow would be our final day on the water, and as the plates were cleared, Diego leaned in with a mischievous grin.

“I have a surprise for you both,” he said. “We need to leave early tomorrow morning, as the place we’re going is about an hour away.”

Peter and I exchanged a curious glance. Whatever Diego had planned, we knew it would make for a memorable finale.

The Final Day

We were out the door well before sunrise, headlights slicing through the still darkness as we rolled south through the countryside. Today’s destination lay far beyond the now familiar mountains of Cistierna, well south of León and deep among the rolling farmland and vineyards.

After about an hour on the road, the first hints of dawn began to glow on the horizon. We turned off the main road, passed through another sleepy rural village, and wound our way across a patchwork of fields and pastures before finally pulling up beside the river.

The Esla here took on an entirely different character. Broader, and more pastoral. We approached the water as tendrils of mist curled and drifted across the surface, the air cool and heavy with the scent of wet grass and livestock.

As we rounded a small island, a long, deep, turbulent run came into view, unmistakably fishy water. I noticed Diego had brought along a second rod. “Some great nymphing water here,” he said, giving a half-smile. “We’ll work this on the way back out, if things don’t go our way.”

For this self-confessed dry-fly addict to suggest subsurface tactics spoke volumes. Though our trip had been memorable so far, the fishing had tested us at every turn, and Diego clearly wanted to give us the best possible finish.

We pressed upstream. Above the deep run, the river split neatly in two — an enormous gravel shelf dividing the current, with slow glides along the left and a faster, riffled channel spilling down the right. As we paused to survey it, Alain suddenly gestured ahead. A rise, faint but definite, rippled the calm water near the far bank. Without a word, he peeled off to make his approach.

Peter and I carried on, scanning the glassy surface for signs of life. As the sun began to warm the valley, the first pale mayflies started to appear, drifting lazily downstream. The fish noticed too, soon a handful of subtle rises dimpled the surface. Buoyed by the sight, Peter and I split up to cover more water: he took the slow left channel, and I worked the faster right.

It wasn’t long before Peter was in. His rod arced gracefully, and moments later a stunning wild brown trout slipped into the net, a picture-perfect fish, and a promising start to our final day.

Every now and then, the calm was shattered by a great splash from farther upstream. In a wide, shadowed pool about two hundred yards ahead, large fish were moving, occasionally leaping clear of the water, flashing golden flanks in the sun before vanishing again. Diego gave us a knowing nod; that was where we’d end up.

As we crept closer, the rises tapered off, and the pool seemed to retreat before us. No matter how far we walked, the activity stayed just out of reach. The water here was glassy, shallow, and unforgiving, each step a gamble that might send ripples skittering ahead to warn the fish.

I spotted a few trout in the shallows and took a couple of careful shots, but they scattered the moment the leader touched the water, ghosts in liquid glass. The sun climbed higher, the bite of morning faded, and I paused for a sip of water. Behind me, Peter stepped into position at the head of the pool and began to cast.

Dark ArtS

We spent another hour working the pool, casting and re-casting with growing futility. The sun climbed higher, the morning haze long since burned away, and even the river seemed to settle into a lazy indifference. Eventually, Diego checked his watch and gave a resigned shrug.

“Let’s make our way back,” he said. “Maybe we’ll try that nymphing run from earlier.”

Peter and I nodded, a change of pace felt right, and we began the slow walk downstream.

We eventually came upon El Cormorán, perched on a small island like his namesake bird, cigarette in hand, staring into the middle distance with the air of a man freshly humbled.

“¿Qué pasó?” Diego called.

Alain sighed, exhaling smoke. “I spent all morning stalking one fish,” he said. “Big one. Fifty centimetres, easy. Finally got him to eat… then snap.”

He mimed the line breaking and shook his head, half in disbelief, half in amusement.

We offered our commiserations, every angler knows that sting, and traded stories from the morning before Diego handed me the long 10’6” nymphing rod. He nodded toward the fast channel. “Your turn.”

Now, while our hosts were dyed-in-the-wool dry-fly addicts, I was anything but. The dark art of Euro-nymphing was my comfort zone, the same tight-line tactics we used back home for yellowfish. Diego opened his fly box and selected a pattern with a small flourish: the quintessential Spanish nymph, a silver-beaded perdigón.

I tied it on and confidently approached the run. Deploying my finest tuck cast, I began plumbing the seams, working from near to far.

“You’ve done this before,” Diego remarked with an approving nod.

The water looked perfect; a deep, fast run flanked by soft edges scattered with boulders that screamed holding lies. I worked it methodically, seam by seam, searching every pocket. Nothing. Not a twitch of the sighter.

I adjusted, fishing higher in the column. Nothing.

Switched flies. Nothing.

Changed angles, depth, pace. Still nothing.

The current murmured on indifferently, the perfect run proving utterly lifeless.

Eventually Diego waded up beside me, a puzzled look creasing his brow.

“I don’t get it,” he said quietly. “You fished that water perfectly… not even a sniff?”

He looked genuinely disappointed, though the frustration wasn’t directed at me. I tried to lighten the mood.

“Must be operator error,” I said with a grin.

He shook his head. “No. They’re just not on today.”

And that was that, the unspoken truth every angler eventually accepts. Sometimes, no matter what you do, the river has the final word.

We trudged back toward the cars, boots squelching through the soft gravel, bellies rumbling and spirits oddly content. Lunch, and perhaps a cold beer, beckoned, and the Esla flowed on behind us, secretive as ever.

Cueva San Simón

For our last lunch of the trip, our hosts had something special in store. After a 15-minute drive, we pulled into a small, unassuming country town. On the outskirts, nestled into a gentle hillside beside the road, we noticed a series of strange little doors, each painted a different colour, no two alike. Some were freshly painted and well-kept; others sagging and weathered with age. The whole scene looked more like Hobbiton than rural León.

Diego laughed at our puzzled expressions.

“Cuevas,” he said. “Wine caves. The locals dig them into the hillsides to store wine. Naturally cool all year round.”

It turned out our destination was in one of these cuevas, though far grander than most: Cueva San Simón. From the outside, it was an unassuming place, but once we stepped through the humble door, we were met with an astonishing sight: a vast subterranean warren of interconnected rooms, passages, and stairways, all hewn from the earth. Waiters darted between tables, the flicker of candles dancing across rough earthen walls, and the air was thick with the smell of sizzling meat and wood smoke.

“This is one of the most popular restaurants in the area,” Diego said, clearly proud. “Booking is absolutely essential.”

After a quick exchange with the hostess, we were ushered to our table. A waiter appeared and poured us some deep ruby red wine. The first sip was rich and earthy, a perfect match for the cave itself. A short while later, two enormous platters arrived, piled high with grilled chorizo, pork ribs, Angus churrasco, and thick-cut entrecôte, flanked by a generous bowl of fresh salad.

We tucked in with gusto, the chatter and laughter flowing as freely as the wine. As the last of the meat disappeared and coffee was poured, Diego leaned back with a grin.

“Now,” he said, “for this afternoon, we go north. A change of scenery. You’ve fished the Esla…” He paused for effect, “now it’s time to meet her sister, the Río Porma.”

The Last Cast

We drove north for about 40 minutes before Dani pulled the SUV over at a small bridge, giving us our first glimpse of the Río Porma. Smaller than the Esla, certainly, but no less captivating. From our vantage point on the bridge, we could easily spot a number of healthy brown trout feeding in the shallow water, their movements glinting in the soft afternoon light.

A short drive later brought us to the last coto of the trip, situated on a wonderfully intimate bend in the river. One of my objectives for this trip had been to film a short interview with Diego for our YouTube channel, introducing viewers to this extraordinary fishery. On the first day, I’d asked him to think about possible locations, and it was immediately clear why he had chosen this spot: the river meandered calmly, the far bank lined with birch trees illuminated by the waning sun, their leaves swaying gently in the breeze, the perfect backdrop.

Dani, Alain, and Peter headed upstream to give us space, while I set up cameras and microphones. Diego was slightly nervous, fidgeting in front of the lens, and I reassured him that I was probably more anxious than he was, which, truthfully, was very much the case. After a brief bumpy start, we found our rhythm, and the interview flowed naturally. Relieved to have it in the bag, I packed the cameras away so I could enjoy the last few moments on the river. By now the light was fading rapidly, and time was short.

I managed to rise a couple of fish during that final stretch, though neither connected. As the last traces of sunlight danced across the water, a splashy rise beneath an overhanging tree on the far bank caught my eye. I looked at Diego. “Last cast?” He nodded.

To reach the fish, I’d need a downstream presentation, so I waded into position just upstream. The first cast landed short. The next looked promising, and I fed a little slack into the drift, letting the fly carry straight over the trout. Just as I’d hoped, the fish engulfed the tiny mayfly. My heart raced. Surely this was the perfect fish to end the trip on. But as I lifted the rod, the line went slack. Nothing. Perhaps a split-second too slow, or too fast… either way, the trout had the last laugh.

I chuckled and glanced at Diego. “Just my luck.”

He gave me a good-natured slap on my back. “Don’t worry, my friend, you’ll get them next time.”

We returned to the car to meet the others, slowly packing our gear. Pete, Alain, and Dani had each managed a few fish and were pleased with their afternoons. On the drive back to Cistierna, I reflected on the past three days; the highs and lows, the challenges, the small moments of triumph. This trip had been an absolute masterclass in finesse, technique, and keen observation. While the fishing had certainly been tough, I was completely satisfied, knowing I had learned from some of the best and that my skills as an angler had grown immeasurably.

Back in Cistierna, we enjoyed a final dinner together, recounting the highlights of the past few days. Diego insisted we had to return to fully appreciate all the region had to offer, listing off countless other rivers, cotos, and hidden corners to explore. It was clear we’d barely scratched the surface, and the thought of spending a week or more here was tantalizing indeed.

Adios, León

The following morning, we bid a fond farewell to Diego as he departed for San Sebastián to visit his family. We loaded our luggage into the SUV and made our way back to León Station to catch the 10:30 train to Madrid, where Dani and Alain saw us off with hearty handshakes and exuberant backslapping.

The train journey offered a perfect opportunity to hear Pete’s thoughts on the trip. We were completely in agreement. While this certainly wasn’t an “easy” destination, or one well-suited to beginners, it absolutely was for those like us, who were obsessed with fly fishing. Those who are constantly striving to improve all facets of their game, from casting, presentation, and reading water, to nerding out over fly design and the subtle intricacies of various tying materials. This is a place for those that understand that these are incredibly savvy fish, educated by their interactions with generations of some of the finest fly anglers in all of Europe, if not the world. To do well here, you had to become a better angler, no two ways about it. The Esla and its tributaries were a crucible, a dojo, a sanctum of higher learning, and I, for one, couldn’t wait for my next semester.

Before long, we were back in Madrid. Pete and I wrestled our luggage through Chamartín Station one last time before sharing a cab to the airport. I had thoroughly enjoyed meeting Peter, a down-to-earth and insightful companion, and looked forward to sharing rivers with him again some day. I told him as much as we said our goodbyes, then headed for my gate, feeling a touch of melancholy that the adventure was over. After an uneventful flight, I arrived safely back in the UK that afternoon, and was home by early evening.

That night, lying in my own bed, my thoughts drifted once more to the Esla, its crystalline currents slipping through my fingers, the flash of wild brown trout in the sun, the laughter of friends carried down the valley on the evening breeze. I thought of Diego’s patient smile, of Alain’s effortless casting, of Dani’s boundless enthusiasm for his homeland.

Spain had tested me, yes, but it had also changed me. It reminded me that fly fishing isn’t just about the fish we land, but about the moments in between, the quiet observations, the missed takes, the slow sharpening of one’s senses.

As I finally drifted off to sleep, Diego’s voice echoed in my head:

“Don’t worry, my friend… you’ll get them next time.”

For more information about Fly Fishing León please email Alistair Routledge, alternatively you can call our office on +44(0)1980 847389.